I made you a compass

I stay there, hidden, under the desk where no one knows or guesses me. Maybe you pretend you don't see me. I see you, imagine, still sitting in the mahogany armchair. Your thoughts were not (they are not, which I still feel the same today as then) revealing and clear, like the drawings torn from the wood of your armchair. And not even the stern line in the middle of your forehead that made you more fragile, or absent.

Or both. If I smoothed out that grave frizz of time of yours and wiped it off my forehead, you would offer me the most beautiful smile that can be offered to a daughter who did not guess that she was going to lose you. And that, with your loss, I would simultaneously lose the worry of that lost look of yours or the mahogany lines of that armchair of yours (which left after you left because it reminded us how painful your presence was).

Where will this armchair with armrests engraved with art be? On the longest day of your eternal apathy, I remember, with incredible clarity, your cold, icy hand dripping my hair wet with crying.

"How unfair," I cried into the mouth silenced by the others.

"How unfair," the seconds repeated.

Everything remained still, dumbfounded, apathetically still. You inert, in the position of dead, I am dead, I know now, but it was you who were buried and this injustice of robbing us is what killed me. Even today, Dad, even today and 30 years or more ago, I am still dead and unburied. Could this be it, to die and remain uncovered without the vultures devouring us at the first night sign of the end?

Your cut-out profile of a cold, tin-plated floor lamp, where a fainting light lamp projected your nose onto the side wall. Four frames of coal-fired sailboats mingled with the lively movements that were in you.

On the long day of our death, you were restless, but it must have been a kind of prognosis of yours reserved for your sought solitude. Because you exiled yourself from us, reading Tolstoy and cursing this and that in laughter. It was already weighing on your carcass, more than the limiting pathology of a secular and old heart, the dredger of the end. The dagger had done damage long before, and you still stood upright. What stopped you from doing it again? And you lived running, like Sammy, so that you would not be mistaken for a body that drags itself between the pity of some and the despair of others. And loving you has always been so much easier. To love your irreverent ideas, your non-conformism, which kept alive the eyes of those who sought you out and laughed at them so that they wouldn't take you seriously. It's a bad joke that you don't want to be loved, that you kept your distance in the last times before the long day. You were so loved that the heavens closed in, became disjointed, eager to take you away and stifle our pain. Our dreams, if you saw them, crashed like crumpled sheets of paper, turned into nightmares by the law of force.

Dad, you were white, wax, lime, not a drop of blood, and not even Tolstoy telling you stories kept you awake. And death, that black and ultimate thing, with no competence other than that of snatching the living from the dead, did not know how to smooth the crease of your forehead, as I did.

And on the d-day, the day of your departure, I tried to do so once more, when I was allowed to approach the box that led you into the humus-free blackness of the earth. The space that mediated the being lying inside that box (I still see it without color, without consistency and without materiality, my defense, I already know) we had talked, you and I and the mother erupted in a scream of helplessness (you needed to be by her side to comfort her, but alive).

At that moment, I warmed up with love and stroked your cold dead forehead and it seemed to me that I saw you smile. But what did I know of these things of death and end that lie between life and the continuance of it? For me, you know that, you left on another one of your trips to Lisbon, you didn't go in the alpha, because you had to lie down. I now understand the mother's cry, before the farewell of the body, you were going with no return, she knew it, I didn't. Never again. And "never again" in the vocabulary of a happy child to date, was always replaced by "forever". The most you had from me in that goodbye was a see you later, see you later. And the rest of the tears that flowed like unstoppable hot rivers were because I imagined that they were going to keep you asleep in that space of the cramped and obsolete box and were going to send you on a journey that you would not be able to enjoy. And you loved so much to see people and things mix in life with sounds and smells. To know that you were boxed up as a parcel with no destination or a destination to which we had no access (just like all the trips you made on behalf of the opposition party). In the name of freedom. That freedom that has left us captive, with no other choice. We only knew your protection and your love.

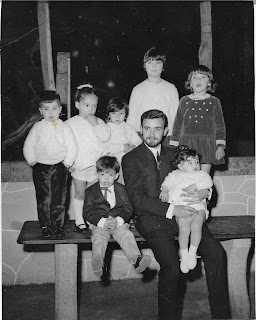

Even today I "see" your office, your desk with 6 drawers on each side, full-bodied and made of mahogany, worked, on a top where the dust was often shaken off by Luzia, from the ashes that scattered from your Ritz, from the tin or thin brass ashtray, with 3 edges, the paperweight with the name of your great-grandfather and grandfather (which I still have) of your eagle. The closet where thick covers were crowded, heavy dossiers, loaded with lives that hung on your back, to your thoughts, wishing you the best and finding in you a kind of messiah. I remember Grandpa Rodrigo's coughs before he left with more papers and menthol candies, the drumming of your fingers when you thought that Mr. Bastos would not know how to solve these lives for you. From your donkey-coloured corduroy jacket when you run away, from the moss-green pullover you were wearing the day you died to me. From the cream shirt, from the bundle of papers you carried in the pocket of your creased farm pants. From your short moustache and your temples where you could already guess the time. That time that wouldn't let your hair turn gray.

You waited until the end of the day to leave, and it was between diapers and potatoes that I left my mother and Luzia in the kitchen and went to take a look at your room. From outside, the street lamps came in and it was these clippings of light that let me see the book half-open on my belly and your arm hanging to infinity from the bed, your eyes open and your forehead creased. Were you calling someone who didn't come or was it just me? You died and I was left unearthed. And with each passing year, with each decade that I survive, I think that staying alive and stuck in moments of pain can be the worst death, the longest and the slowest. I know you're there, always doing everything possible and impossible to get me back on my feet. Other lives will come and in others I will find you. But that's where you stood as a compass. And I'm disoriented.

.webp)

Comentários